There’s something about these multi-coloured cocoons, the plaque on the wall `Judith Scott: 1943-2005’. I adjust my glasses and lean closer, scratching my head and struggling with the notion of an artist not only deaf and mute, but also stricken with the effects of Down Syndrome.

I’m in the New Museum of Modern Art (or `MOMA’), New York City, having first dallied outside on the far kerb, staring at this dramatic offset stack of architect-designed boxes – once a parking lot – before braving Bowery traffic; in 1977 the original Tribeca MOMA being the first museum of its kind in this city since WW2. With more adventurous works not so easily accommodated by conventional museums, the MOMA brief to provide an ever changing ‘exhibition, information, and documentation centre for contemporary art’.

Mid-afternoon I’ve first dropped off my coat at reception, gulping coffee from a paper cup and completing a circuit of the ground floor foyer and bookshop; taking in a wall of giant penis’s – my Christmas visit coinciding with the exhibition `Hard’ – the artist having an interest in the 60s graffiti of men’s toilets. With these, the notes say, the artist discovered a window into the male subconscious. I’m suddenly feeling a little grubby.

From there I’ve taken the lift to the top level – the viewing room – clear across The Bowery and beyond, once the seedier southern realms of Manhattan; the plan being to wend my way downwards, taking in each level.

At first shocked at the `gritty’ 2002 Lower East Side, the architects would later describe their design as a response to that powerful mix; this Bowery incarnation of MOMA opening in 2007 – The Bowery said to be the oldest thoroughfare on Manhattan Island.

From the top I’ve descended to `Come Closer’, an exhibition of all things Bowery circa 1969-1989 – original artwork and performance documentation by artists with a local connection – a place once considered in urban decline, with more than its share of homelessness and drugs; cheap rent nourishing painters, photographers, filmmakers and musicians. A giant autographed picture of the Ramones stares out from a white wall.

From here it’s down another 2-levels and an exhibition `Cosmos’, firstly including the primary artist’s ceramic work pairing sculptures, the organic subjects of reproduction and replication; the other level devoted to works of wool.

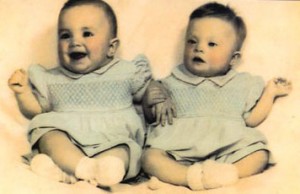

But it’s the next level that’s captured my imagination, standing here among Judith Scott’s scattered creations; a silent netherworld, oddly primitive – reminiscent of ancient Peru or Egypt – materials determinedly sought out and each abstract shape tightly wrapped: strange mummified bodies of work bound in strands of yarn the colours from some magic rainbow. There’s a special intensity, a secret vision I’m privileged to be part of, hours of work by a driven artist.

Back at reception I’m bothered by something that won’t let go. Jeff hands me my coat. “Judith Scott? Ah yes… of course; be happy to help.”

Judith was the twin sister of Joyce, struck down with Scarlet Fever as a kid and losing her hearing. With her deafness undiagnosed, Judith is considered severely retarded and a lost cause. At age 7, her parents – acting on qualified advice – make the difficult decision to send her away.

Jeff stops for a moment; takes a deep breath. “Judith lives in State institutions, separated from family and a loving sister distraught at the loss of her other half.” I put my coat back on the bench. “But in 1986, with the death of her father and her mother’s breakdown, Joyce worked to become Judith’s legal guardian; the sisters reunited after 35yrs apart.”

“Before long, Judith’s enrolled in the Oakland Creative Growth Art Centre, the first in the world to provide studio space for disabled artists.” Jeff tilts his head to one side. “But for almost 2yrs there’s no sign of any artistic interest; until after silently watching the class of a visiting fibre artist one day, Judith is suddenly prompted to start work.”

“So that’s it”, Jeff says, again handing me my coat, “the beginning of the creative explosion you see upstairs; every single piece gathered by Judith, painstakingly wrapped and woven in her own selected colours.” Jeff pauses and I wonder how many times he’s told the story. “You know… Judith alone decided when the piece was complete.”

Jeff leans forward as I don my coat. “In some pieces, Judith hid an amulet, the significance only known to her.”

Judith Scott worked steadily for 18yrs making over 200 pieces – some 3m long, many pieces with a twin – with the complete freedom to use whatever materials she found; her work now all over the world.

In the dark outside, I step carefully on an East Village pavement riddled with ice, still preoccupied with those multi-coloured shapes and Judith’s secrets held deep within.

At my apartment steps I wonder at the lot of the deaf and the mute, and philosophical musings that consider the human mind initially void of ideas; a blank piece of white blotting paper, with everything learned as we stumble along.

Inside I plug in my notebook and browse the website of Judith and Joyce Scott. There’s a quote on the opening page: the words of Art Critic Michael Bonesteel –

‘Making something of nothing, or precisely, luring something from the unconscious and giving it material form is the closest thing to real magic in this world.’

Judith and Joyce Scott (image from Judith and Joyce Scott website)

*** Opening feature image of `Judith Wallace Scott’ from judithandjoycescott.com ***

I am moving my interest in Manhattan further south than I would have just a few years ago, so good on you 🙂 I too was a bit shocked at the grittiness of the Lower East Side, unlike what we would have found in inner Australian suburbs of the same age. And of course we have to make an effort to see The New Museum of Contemporary Art which looks amazing.

But now I am fascinated by the meat packing district, the High Line and the Chelsea Historical District. Not quite the Bowery, to be sure, but fascinating as well. Thanks for the link

Hels

The legendary Chelsea Hotel, New York

http://melbourneblogger.blogspot.com.au/2014/03/the-legendary-chelsea-hotel-new-york.html

Thanks Hels,

& yes, different stories to those of Australian cities of that era. (btw, the High Line really is a the successful realization of a great space.)

Shall have a look @ your post on The Chelsea.

Sorry to have been away from your blog for so long, I remember now how much I love your emotive writing. Great post.

Hullo Dale!

Thanks for the kind words.

Ian, thank you for sharing this with us. Judith Scott was such an incredibly intense and vivid artist. Doing what she did deaf, mute, and with Down Syndrome is amazing, and her story is truly inspiring. So many of us with so much more do so much less. I admire Joyce too for reuniting with her sister and encouraging Judith’s art. I love the rich colors and imagery of her cocoons. In that photo of her hugging a cocoon, it’s as if she is becoming one with her creation; those cocoons are her soul, her spirit. That quote from Michael Bonesteel is perfect; yes, “making something of nothing…is the closest thing to real magic in this world.”

MOMA is such a unique and fascinating museum. LOL about the “Hard” exhibit and giant penises! I haven’t visited MOMA in many years since I moved away; I really need to go again. Great post.

So glad you enjoyed the read JL… you are always so encouraging.

I should have guessed you’d be familiar with MOMA.

I’ve never been to MOMA, and would love to visit it. What a cool collection of work by Judith Scott, and a wonderfully inspiring story of sisterly love. I love Bonesteel’s quote about how making something from nothing is the closest thing to real magic in this world; as an artist, I totally agree.

A constantly changing exhibition, I’d be back there on every visit Kris. Quite a place… the building included. I’m quite sure you two would be impressed.

What a fascinating story about Judith Scott. Thank you so much for sharing it with us. Side note: I giggled when I read about the penises. 😉

Thanks Janene, so glad you enjoyed the graffiti.

Ian, thanks for introducing me to Judith’s work. Proves that art comes from a place much deeper than the rational mind. The creation of art, like that of life, is such a mystery.

Such a mystery indeed NP… much appreciated.

Thank you for dropping by.

Ian. I am mesmerized by those surrealistic cocoons vividly described by you. What sensibilities, what pain, what fear, what urge to protect they encapsulate? The title of the story is symbolic of the life of the deaf and mute artist. It is a tale that will linger in my mind.

Ah yes Uma…

A special artist & great motivation for a story.

Thank you so much.