The plaintive cry of a lone peacock fractures the silence. Croaking egrets chorus from clumps of reeds at the foot of these stone walls and ramparts. There are snorts and bellows from buffalo. Two calves splash about, the mother’s wet horns and back steaming above broken reflections that come and go between drifts of morning mist.

I stand on the edge of a translucent marble plateau; the Taj Mahal. My friend smokes one cigarette after another. This is the calm, he says, “before the throngs of tourists that will come, as surely as the monsoon.” I lower one hand over the edge and run my fingers along the carved railing. The sky is flat and dull, the railing cool.

At our backs are the marble minarets of the most visited place in India – the eighth wonder of the world – built by a broken-hearted visionary for a loving wife who died during the birth of their fourteenth child. And yet Ishmael and I choose to ponder the ways of a river all smoke and mirrors; a timeless highway meandering through the valley.

Ishmael is an accountant – university trained – and working in the ticket office. He’s dark, with bloodshot, wandering eyes and a ragged lop-sided moustache; his hands nervous and nicotine-stained. He has a smoker’s raspy cough and the brooding air of a worn-out man. The dank odour of river mudflats and the fragrance of orange blossom mix with the smell of his Capstan cigarettes.

To get here we’ve ambled along paths, through ornamental gardens and ponds in the pre-dawn cool. I’ve followed behind without a word as Ishmael completes his daily routine, to the rhythmic sound of his own scuffing sandals and the clipping and sweeping of an army of groundsmen.

“Once upon a time there was a little girl,” he begins. “Her name is Aastha. She is feisty, bright and beautiful, with the thickest straight hair, like her mother. And her eyes, they shine. When she laughs, even the thrush stops its melodious whistle. It is a proud bird, the thrush, and is not liking to be outdone.”

“One day the girl, she is poorly. Over many weeks she is not better. And now there are tantrums, then silence. This little girl is aged 12.” Ishmael coughs. “The parents, they take the girl to the doctors in New Delhi. There are questions, prodding and poking.”

“Finally there is coming an answer; but the parents, they are frightened.” Ishmael stops and looks down at his hands as if they belong to someone else. “If only there is a magic carpet to take them away to start a new life.” Ishmael’s eyes lift for a moment. “But of course, there is not such a thing. Is this a curse for something they have or have not done?”

Ishmael lights up yet another cigarette, blows out a streak of smoke and continues. “There is chemotherapy and the many tests. The money comes; everyone, they are helping. One day the results will surely be better.”

Ishmael turns to face me. “There are books and many learned people here,” he says. “This is the new India, the motherland of opportunity.” But there’s a hollow ring to Ishmael’s words and his voice fades away. “But, can it be the new ways are not always the best? The mother, she pleads to do the needful; to consult the mullahs, the priests and holy men.” Ishmael turns, gazing across to the mosque. “Here, we have the prayers of many faiths; in the temples, fire temples and gurdwaras. We have churches, idgahs and synagogues. But still, where is the answer?” Ishmael takes a resigned breath. “There is a loving grandmother, and many aunts. There are silent and tearful hugs for a little girl with no hair. “But the painful tests, they are continuing. Needles puncture skin and bone. Precious marrow is sucked from her tiny pelvis. But this girl, she is so very brave.”

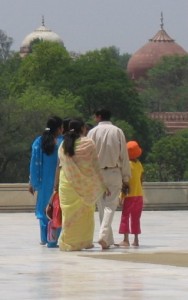

Ishmael’s stare returns to the river and my thoughts are disrupted by a sound; the gleeful chuckle of a small girl. A family are the first tourists, the girl dressed in a yellow tee, orange towelling sunhat and bright red beach pants. She draws imaginary pictures with her foot; the marble tiles polished by a million feet before her.

Ishmael draws in a deep breath. “Month after month, they go by. Finally it is all too much, even for the bravest of little girls. There is crying when she thinks her foolish father cannot hear. Aastha hides in the corner of her room chewing at the sleeve of her favourite dress. She is tired.”

Ishmael shrugs his shoulders and sighs. “But her father, he is always knowing the best; a selfish man, he cannot let things be. To lose his Aastha is more than he can bear.”

He turns towards me and I read the lines weathered in his whiskered face; there’s an empty greyness in his eyes to match an empty sky. “A house without children is a graveyard,” he finally says. Today would have been his daughter’s sixteenth birthday.

Suddenly we’re surrounded by hundreds of tourists. Ishmael’s working day has begun. We say our goodbyes, and I watch as he descends the stairs. He continues past fruit trees and the cypress rows of classic Persian design – trees of life and death – until he is lost in the crowd.

***

That night I journey to Delhi, climbing aboard the eight-thirty superfast train – the Shatabdi Express – to mix with `bank managers and army officers’ according to the railway brochure. But I’m not good company, picking at a cucumber sandwich and swigging from a bottle of Kingfisher beer.

Fields flash past. But the twilight is ebbing as I stare at a landscape easing into night, until there’s only the faded reflection of a little girl’s laughing face. Yes, her eyes are shining jewels, and around her neck is the scalloped lace collar of a floral dress. Her Indian name means `faith.’

Faith in Family – the Taj Mahal, Agra, India

*** First appearing in `Indian Summers’ a book by Ian Cochrane, published by Wordy-Gurdy Press 2011 ***

Beautifully written piece, Ian. I love the vivid imagery that transported me to the grounds of the Taj Mahal, a place I’ve always wanted to visit. Immediately, from the first paragraph, I could sense the sights, sounds, and smells as if I was there. I thoroughly enjoy the way you set a scene.

Ishmael’s poignant story of his lovely and brave Aastha both moved and saddened me. Oh, how I wanted a miracle for her. When you write, “there’s an empty greyness in his eyes to match an empty sky,” I could feel the deep pain in Ishmael’s soul. The image of him leaving you, walking past the “trees of life and death” and blending into the crowd was perfect in its symbolism and simplicity. We move on, life goes on, but we never forget the lives of those who have touched us, especially loved ones. Your last paragraph was beautiful and truly brought the whole piece together. “Her Indian name means ‘faith,'” how fitting!

I also love the photo of the family with their little girl in colorful array looking outward to the Taj Mahal. The words, the photo, it all flowed beautifully in your post.

Thank you Madilyn. You miss none of my arrows.

Thanks again.

Ian, this powerful story of yours, told with your usual subtlety, layers of meaning and attention to detail, had me in tears. You simply and beautifully weave your tale in almost matter-of-fact fashion and leave emotion to the reader. One senses immediately in the first two sentences your love of language, your delight in words, with their almost brazen use of alliteration.

Much appreciated NP.

I try & `feel’ the moment as I go.

Thanks.

A very well written and interesting story, it brought me back many memories of being in Agra myself a couple of decades ago. Loss is something very difficult to deal with, a trip to Varanasi once a long time ago made me realize it is inevitable, though we may never want to say goodbye, in the end we all leave this world alone.

Yours comments are very much appreciated PB.

Yes, it seems you & I share the same feelings for India. No visitor could walk away unaffected.

Thanks for dropping by.

It was as if Ishmael just took leave of me, weaving his path through the throng of tourists to Taj Mahal. The imagery of the river corresponds to the mood of the story. The contrast provided by the small girl dressed in yellow, orange and red accentuates the tragedy.

It is a brief and unforgettable story, like the life of Astha.

There are times I lose my faith too.

Thanks Uma,

I did choose your Taj Mahal as the site for that story, as I imaged it would add to the depth of the story. So glad you liked it, & I’m not surprised you picked up the light & shade in the piece.

This compelling story flowed marvelously, completely transporting me to another place and time. It really resonated with me, pulling me in. I could even smell Ishmael’s cigarette smoke and hear Aastha’s brave laughter. Fearing the loss of a child is something I understand too well. My sons both have cystic fibrosis, which is still considered terminal, although the life expectancy is now mid 40s. The way I deal with my fears is to stay in the moment, and enjoy every second of our time here together.

Hullo Kris, & thanks.

Yes, I’m sure anyone with the sort of fears you have re: your sons would certainly relate to the story. Making the most of every moment is definitely the way to go.